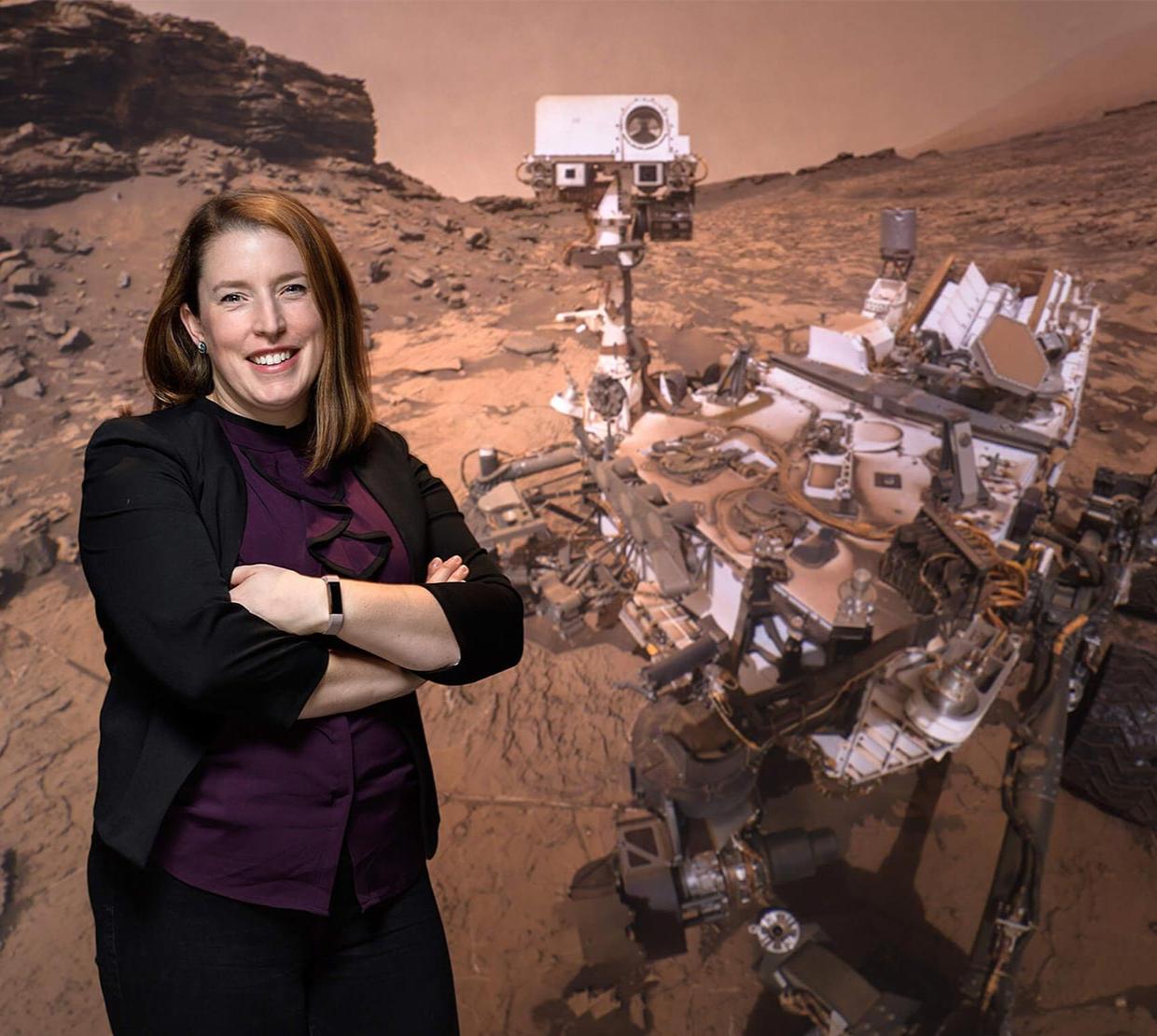

How do you pick the one location on an entire planet to look for signs of life? That was the question that Oregon State alumna Briony Horgan (B.S. Physics, ’05) and her team were tasked with solving in the years leading up to the NASA Perseverance rover landing on February 18, 2021.

Horgan, an associate professor of planetary sciences at Purdue University, leads the mineralogy research portion of the Perseverance mission. She first joined the Perseverance science team in 2014 in the midst of an exhaustive five-year study of 60 potential landing sites on the Red Planet. “We know we might only have this one chance to do this, and it was tough to select the site,” she said in a Purdue University article about the mission. “If we had to choose just one spot on Earth to gather all the data about the entire history of the planet — well, where would you go?”

Ultimately, Horgan’s research was a key component in their decision to explore the Jezero Crater. “We think Jezero Crater is the best location to search for evidence that life existed on Mars, if it ever did,” she said. “And what we find will help us learn more about whether or not we are alone in the universe.”

“The place we’re going on Mars, no human eyes have ever seen before”

Jezero Crater is a 20-mile-wide area located within the Isidis Planitia region where scientists believe meteor impacts once created conditions suitable to life. Spacecraft imagery suggests that more than 3.5 billion years ago, water flowed from river channels into the crater and created a lush river delta and a lake that once held as much water as Lake Tahoe.

“The place we’re going on Mars, no human eyes have ever seen before,” she said. “I can’t wait to get onto the surface of the planet and see a new place for the first time through the eyes of the rover.”

A planetary geologist, Horgan led a study of the mineral diversity in Jezero crater, finding evidence of a “bathtub ring” of carbonates around the edge of the former lake. “This is really exciting because that’s exactly the kind of place you would look for microbial biosignatures from a lake on earth.”

In summer, 2019, Horgan and her team traveled to Turkey to explore unexpected parallels between Jezero Crater and a similar landscape on earth: Lake Salda. Known as an analog environment, Lake Salda is the only lake on earth that contains carbonate minerals and depositional features (deltas) similar to those found in at Jezero Crater. Hydromagnesites at Lake Salda, similar to the carbonate minerals detected at Jezero, are thought to have eroded from large mounds called ‘microbialites’ – rocks formed with the help of microbes. The discovery gives them hope that a similar process may have occurred on Mars.

"This landing site is exciting because we have really clear evidence that this ancient lake existed, that it had persistent liquid water for a long enough time to create this ancient delta, and that there was enough water flow to overflow out the other side to create the outflow channel,” she said. “This suggests that the lake was a long-lived and stable environment that could have been inhabited by ancient microbial life."

A historic mission

NASA has sent five different rovers to Mars, with the first landing in 1997—Sojourner, Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity and now, Perseverance, which launched on July 30 from Florida’s Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.

Perseverance traveled through space for 204 days, reaching the Martian atmosphere at a speed of nearly 12,500 mph. Since it typically takes 11 minutes for a radio signal to travel between Earth and Mars, the rover had to complete landing on its own.

“The rover descends in a plasma fireball through the Mars atmosphere and has to slow down from about 12,000 miles per hour to zero in about seven minutes, so it is a pretty scary endeavor,” she said. “It’s so hard to land on Mars,” she said. “But really, everything was almost perfect. It went almost better than we could have hoped.”

On Mars, Perseverance will spend its time taking photographs, video, pulverizing rock by shooting lasers (so that scientists can determine the chemical composition), using microscopes to search for organic molecules, drilling, analyzing and doing a variety of science chores. This will produce enormous volumes of data that will take the scientists years to analyze.

For the first time, the rover will also collect samples to bring home to Earth. NASA plans to send a return mission in the next decade to retrieve the samples, which will be stored in Perseverance. “It’s possibly the only chance we’ll ever have to get to do both of those things, especially the sample return,” Horgan says. “It’s really hard to do, and it’s expensive.”

"This mission could tell us whether or not there is life elsewhere in the universe, and that’s one of the most important scientific questions we could hope to answer"

“Bringing samples back from Mars would be amazing,” Horgan says. “It would not only be a feat of engineering to retrieve the samples and return them, but it would be the first time we would have samples brought back to Earth from another planet. That would be quite historic.”

Native to Portland, Oregon, Horgan fostered a passion for geology from an early age, surrounded by the unique geography of the Pacific Northwest.

“Geology was something I absolutely loved because it explains how the world around us came to be over millions and billions of years,” Horgan said. “Doing that in space is even more interesting because the time scales are even more crazy. On Mars, we’re talking about 4 billion years of evolution that produced the rocks we see.”

“It’s a huge responsibility to be part of this incredible mission,” she said. “This mission could tell us whether or not there is life elsewhere in the universe, and that’s one of the most important scientific questions we could hope to answer. To be able to contribute in any way is just a huge honor.”

Sources for this story include news releases and profiles of Horgan courtesy of Purdue University.